China and its Infrastructural Investments as a Neocolonial Actor in Rwanda

Julien Derroitte

Fall 2024, Politics of Developing Nations

Introduction: The BRI as the Tool of the Chinese Neocolonialism in Africa

China has a growing interest in the global stage as an investor; most notably it has invested over US$1 trillion for the advancement of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI, formerly “One Belt, One Road” [OBOR]) (Wong 2023), US$679 billion of which it has spent in infrastructure projects along between 2013 and 2022 (U.S. GAO 2024). It is, thus, critical to examine how Chinese money, now saturating a majority of developing nations, could affect those countries’ development. Of this US$679 billion, the 5 largest BRI sector engagements (from highest to lower USD investment) include: energy, transport, metals & mining, real estate, and technology (“China Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) Investment Report 2023,” Wang 2024). Note that each one of these, excluding technology, have significant spatial manifestations–each classified as “heavy civil infrastructure” project sectors. Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) is one of the initiative’s largest targets with 25% of countries which have joined the BRI belonging to the region (“Countries of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI),” Wang 2024); of the 55 African Union (AU) countries, 53 have joined.

SSA is currently one of the most underdeveloped regions in the world. According to the United Nations Development Programme’s Human-Development Index (HDI), SSA scores the lowest among all regions of the world and of its continent (UNDP 2024). Among issues of gross domestic product (GDP) growth, imminent debt crises (Brahima et al. 2019), underdeveloped social services, and crumbling infrastructure, SSA has consistently relied on foreign investment to stay afloat. Taking into consideration the nature of Chinese interests in Africa, infrastructural investments are some of the most important to consider. Bear in mind the damning reality that Chinese construction firms–which are the only employed engineers and contractors for BRI projects–are considerably unequipped with adequate knowledge of construction in foreign countries, have been found of numerous forced labor abuses (Kuo & Chen 2021), and have histories of shoddy BRI projects which years or even decades later suffer from collapse and dilapidation (Dezenski & Birenbaum 2024) despite often working with local actors.

To analyze the BRI’s implication for SSA, this paper will focus on Rwanda, which is currently the highest scoring country on the Africa Infrastructure Knowledge Program’s (AIKP) African Infrastructure Development Index (AIDI) of all land-locked Central SSA countries (ADBG 2022). It is critical to recognize that Rwanda, like all other countries in SSA, were fully destabilized by colonial rule with 90% of the region existing under the control of Europeans by 1914 (Council on Foreign Relations 2022). Furthermore, Rwanda’s close and highly sought-after ties with the People’s Republic of China (PRC), beginning as soon as 1971 (Gierszewska 2020) reveals a general trend in Sino-African relations, and, more specifically, turns a blind eye to exploitative projects which directly come from colonial developments. I argue that where colonialism caused a damaged cultural and infrastructural history in Rwanda and, furthermore, fueled instability and forcible underdevelopment, current predatory neoliberal foreign investments–primarily from the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)–are a growing, yet highly welcomed by Rwandan governmental actors, neocolonial force realized especially through the funding of infrastructural development.

Histories of Colonialism, Orientalism, and Initial Chinese Involvements

To begin, it is important to understand how colonial history in Rwanda destabilized the region culturally, economically, and infrastructurally, and how orientalist perspectives which drove wounds of ethnic divisions set the stage for neocolonialism in Sino-Rwandan relationships. Colonialism is the act of a nation taking direct or indirect control of a formerly independent land economically, socially, culturally, and politically. Orientalism, which was the most broadly applied method of justifying colonialism, is a framework which sees the developed world as positive and developing nations as negative, prominently through racial division agendas.

Prior to any colonization, Rwanda had signs of societies as early as tens of thousand of years ago, discovered through remnants of Stone Age technologies, then of ceramics, and later an Early Iron Age. These populations slowly grew until by the seventeenth century, the peoples of Central Rwanda were primarily farmers and cattle herders (Vansina 2005). This was due to the mountainous region’s disposition towards agricultural pursuits: from moderate temperatures, rich soils, and reliable rainfall, agriculture has been so sustainable for the region that the sector currently contributes to 35% of the country’s GDP and employs 70% of its labor (Republic of Rwanda 2024). It furthermore creates an economic dependence on the sector which informs China’s interest in the sector, especially as related to their food insecurities. Pre-colonial labor was male-dominated and followed familial hierarchies in which lineage all lived under one roof. Families and village organizations remained distinct, but as time progressed, many began to mix (Vansina 2005). It was during the same century that the Nyiginya Kingdom, ruled by Mwami (king) Ruganzu Ndori, emerged. Although many other Great Lakes region (which currently includes the Democratic Republic of the Congo [DRC], Zambia, Tanzania, Malawi, Mozambique, Kenya, Uganda, and Rwanda) kingdoms formed in tandem, the Nyiginya was the first to establish and deploy a large militarized force–significantly helped by the heavy concentration of people in the region. Along with political centralization towards the king, Rwanda’s expansionism pushed its boundaries far into the reach of present-day territories of the DRC and Uganda (Reyntjens 2018).

Colonization of Rwanda began in 1897, 6 years after the German East Africa Company (in German: “Deutsch-Ostafrikanische Gesellschaft” [DOAG])–which laid its groundwork for expansions in Africa, especially in competition with Belgian interests which had presence in the area at the same time–in cooperation with the German Army, suppressed revolutions against its territorial expansion and established rule (Städtische Museen Freiburg 2024). Knowing that they could not capitulate Rwanda to the Belgians but could also not defeat resistance from the armies of the kingdoms in the region, Germany instead sought alliance with the Rwandan kings. The German colonial spread, importantly, was the first colonizing force in the country; Marco van der Heijden (Heijden 2010, p.15-17) writes that the country’s “high altitude, large population size and moderate climate made Rwanda an attractive colony”–so much so that they planned construction for a stand gauge railway (SGR) which would “connect Rwanda to the world economy in order to promote trade and prosperity.” This SGR included corridors that would connect Kigali from a station near Lake Kivu through both Southern Uganda and Northern Tanzania until reaching the Indian Ocean in Eastern Kenya and Tanzania (Kiriama 2024). These corridors were initially planned to serve the German colonizers by facilitating the exportation of labor and commodities. Although the DOAG railroads which successfully completed construction in 1914 only reached as far as Kasese in Uganda and Kigoma in Burundi, roads were constructed off the primary Dar es Salaam-Kigoma corridor to reach Rwanda. Its completion hinged on the Chinese government which invested after the German colonial forces had left the country. Beyond desires to export the large and dense population to work on soil-rich plantations in neighboring countries (Ibid.), this reveals that the colony preferred indirect rule–a form of control hinging on colonizers employing, forcing, or manipulating local leaders, power, and other individuals to execute the desires of the colony–which lead them to involve themselves in a significant number of infrastructural projects which would use local labor for the colonizer’s economic benefit. In the case of the DOAG, economic development for Rwanda–primarily in the form of coffee and cattle exports–was not desired by other developed nations and dreams of an Imperialist future with direct benefit from Rwandan labor made no progress (Dorsey 1983). Further SGR expansion which was given the go-ahead between late 2023 and early 2024 (PIDA 2024) hinged on funding from the PRC’s Import-Export Exim Bank being newly approved (Anami 2024, Preston 2024). This trend of Chinese investment slowly seeping into uncompleted or extensions of colonial projects will continue to grow from this point onwards; we will address how this will designate the PRC a neo-colonial force later on.

Rwanda, which fell within the DOAG’s 13th district, was, however, only accessible through the city of Usumbura in Burundi (also the military center of the DOAG)–as it was otherwise blocked from access by the Kagera River and region. Thus, by the time the First World War broke out, Germany had little means of resistance against Belgian forces moving through Tabora into Rwanda. When German colonies were redistributed after the war, Belgium was granted control of both Rwanda and Burundi in 1919 by the League of Nations–a guarantee which was reinforced by the United Nations (UN) after the Second World War in 1946 (Baker 1970). Unfortunately for the Belgians’ imperialist and expansionist dreams, they did not acquire the far-eastern boundaries of Rwanda, which encompassed a critical port, in addition to the Southern banks of the Congo river–these were instead granted to British forces (Dorsey 1983). By this point, the country was extremely dense and overwhelmingly agricultural, and with little left behind by the indirect German rule, Belgium quickly defaulted to the same control method. Beginning in 1919 and 1925, Belgium used direct rule by indiscriminately assigning military personnel to fulfill mundane tasks like serving on courts, as police officers, counselors, troubleshooters, and more. It was not until they established control over Akazi chiefs (local leaders which decided what adult males could participate in which public works projects) that Belgians, in transitioning back to indirect rule, were able to make progress on more adequate infrastructure–primarily transportation (Dorsey 1983, REB eLearning 2021). Unsurprisingly, Belgian colonizers exploited Akazi as a forced labor method; in addition to forcing men to work on plantations, Belgians used the forced labor to launch a road construction program among other infrastructural projects (REB eLearning 2021). This indirect yet imperialistic control remained throughout Rwanda’s Belgian colonial history–so much so that by the ending decade of Belgian colonial rule in Rwanda, expansion seemed ever-developing. According to a ten-year plan for economic and social development in the Belgian trust territory of Ruanda-Urundi published in 1952, Belgians saw a future for a “healthy” and “educated” society (Belgium: Ministère des colonies 1952). The difficulty, however, is that alongside racist vocabulary and distinctions, the text heavily emphasizes a desire to solidify Belgian control over Rwanda. The text first emphasizes European education systems, cultural activities, and societal organizations, including french and flemish schools (Belgium: Ministère des colonies 1952, Baker 1970), media, sports, libraries, “clubs for ‘advanced” natives, and more–institutions throughout the African colonies was a weapon to ingrain and legitimize pro-colonial and imperial sentiments; second, numerous transportation modes and systems including roads, waterborne channels, and air travel; third, town-planning organizations which overwhelmingly prioritized market-based efficiency in agricultural commodity production, including silos, warehouses, freezers, oil tanks, crop farms, fish farms, energy, communications, and more; fourth, an expansive agenda for increased mining operations; and fifth, development of scientific studies, primarily in agronomy so as to improve yield for exports (Belgium: Ministère des colonies 1952).

Orientalism was one of the largest tools exercised by the Belgian forces, which “reified, racialised and institutionalized identity divisions, creating a privileged class firmly bounded by identity status” (Purdeková & Mwambari 2021, p.19-20) called the “Tutsi” people. This was one of three broad classifications the Belgian invented: Twa, Hutu, and Tutsi, which were determined by way of false class designations and appearances. In fact, as Layota Matthews Burns (2014, p.9) writes: “physical characteristics that Europeans used to define the groups were not concrete and were not exclusive only to one particular group.” Furthermore, the classifications have little relation with the histories of Rwandan communities and peoples (Newbury 2001), which underscores how Orientalism–specifically the Hamitic hypothesis proposing Tutsis as a “superior race” (Zadi 2021)–obsessed itself with the establishment of “positional superiority” (Said 1978), thus becoming dominant tool in justifying the division, conquest, and “civilization” of African peoples. “Civilizing missions” like these were used to justify Rwandans being consistently tied into the construction and success of infrastructural projects, like providing colonizers with oral knowledge regarding qualities of the land and physically executing construction plans. However, they rarely saw benefits of the infrastructure. Furthermore, insofar as these construction projects progressed, local populations rarely if ever were given a say in the development of Belgian projects. Furthermore, they suffered from its failures, like in the 1943 Ruzadayura famine, when an overinvolvement by Belgians’ relying too heavily on Western crops (Pottier 2002), killed an estimated 36,000-50,000 Rwandans, or between one-fifth and one-third of the regional population (Singiza 2012). With many of the projects of this ambitious plan having been completed or in progress by the fall of the Belgian colony in 1962, the frameworks for exploitative practices and omnipresent colonial infrastructure had already left a wound of Rwandan development. This infrastructure is largely what stunted it from further development and growing tensions, as will be further discussed, contribute heavily to the instability of the post-colonial sovereign region (Baker 1970).

China’s Military and Infrastructure Interests

Before diving into current Sino-African relationships, let’s return back to Chinese interventions in Rwanda and broadly in Africa; this topic is critical to understand why the PRC sought ties with Rwanda and vice-verse in the first place–as underscored by the CCP’s insistence to censor any mention of Chinese involvement in Africa prior to the formal ties established in 1971. Chinese presence, beginning in the form of funding and training, was present in Africa as soon as the early 1960s (Cohen 1973). Rwanda was one of the first countries in which China intervened, with Inyenzi rebels–which grew in man and fire power south of Rwanda’s border with Burundi between 1959 and 1963–being trained and armed by the CCP as early as 1963 (Baker 1970, Stapleton 2017). Much like the postcolonial framework would predict, the country–in its reliance on Belgian forces to repel the 1963 Bugesera Invasion waged by the Inyenzi, the following deterioration of relations between Rwanda and Burundi, and, thereafter, the collapse of the BERB franc (currency circulated by the Banque d'Émission du Rwanda et du Burundi [BERB] since Rwanda-Burundi independence), forced them into a state of isolation (Baker 1970). Furthermore, despite the uptick in violence and tensions in Rwanda beginning in 1959 forcing between 100,000 and 300,000 (primarily Tutsi) individuals into exile into surrounding countries, Belgian liberating forces were welcomed as heroes (Prunier 1997) and President Grégoire Kayibanda’s popularity grew (Mayersen 2015) despite offering little in development for the country in its solitude. With “anticolonialism… out of the question” (Prunier 1997, p.58) and Rwanda’s western and southern borders (DRC and Burundi) stuck in a state of conflict and chaos, Belgian companies were effectively granted monopolies to reconnect the country with the only trade routes available in southern Uganda. The roads were poorly constructed and, despite crumbling under the pressure of such heavy vehicle traffic, they were continually used (Baker 1970).

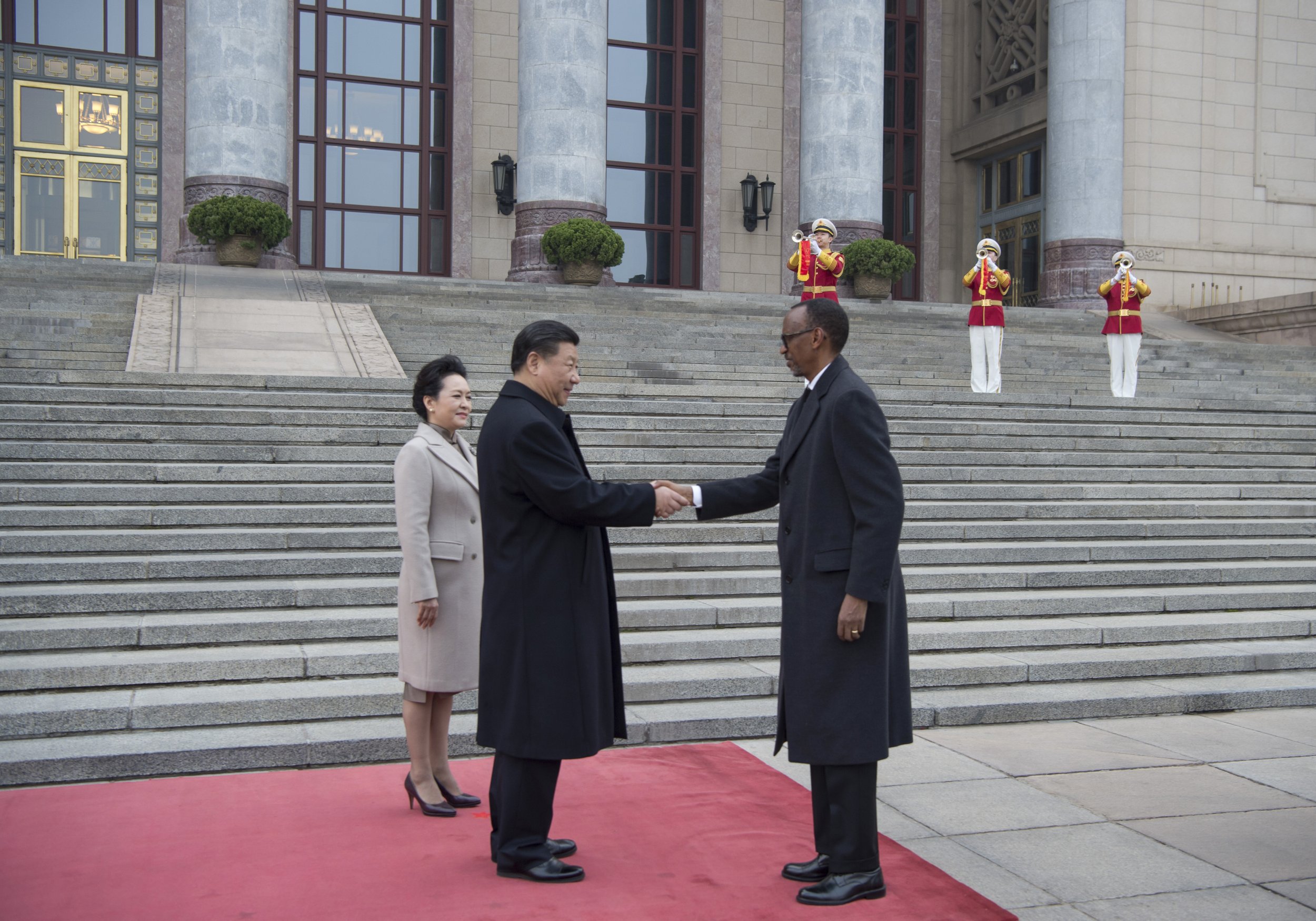

In addition to later providing light arms and machete sales to Rwandan rebel forces, the PRC would join other nations in standing by as the Rwandan Genocide of 1994 progressed. While these arms trades were not explicitly aimed to incite genocide within throughout the nation, their effects proved to set Rwanda back and cause significant destabilization within the region. The Forum for China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC), founded by the PRC in 2000, just 6 years after the Rwandan genocide, was designed as a trade-focused counteraction to other emerging connections with Africa, including EU-Africa, India-Africa, and Turkey-Africa summits and organizations (Murphy 2022, p.58-59). However, Paul Nantulya (2024) argues that “FOCAC has increasingly taken on military dimensions” considering the growing involvement of the People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA: the CCP’s military wing) in executing FOCAC budget allocations in the form of “military training quotas, credits for military sales, and peacekeeping and counterterrorism capacity-building.” China finally confirmed these desires formally in the latest FOCAC summit in which leader Xi Jinping FOCAC’s efforts to China’s Global Security Initiative (GSI); much like Rwanda’s colonizers indirectly wrangled African armies, the PLA is essentially gunning to monopolize African military investments to become the dominant security force in Africa. FOCAC continues to push China’s decade-long military involvement in Rwanda and Africa generally as it now seeks to protect BRI infrastructure investments, unpaid debts to China, and import-export freedom (Peltier 2020).

The BRI was a program launched shortly after FOCAC as China’s globalized agenda to invest in infrastructures around the world. It was and continues to be a largest doctrine expanding its economic desires outside of its border. For this sake, it is looking to create a level of interdependency between China and the developing world (Jie & Wallace 2022), something which comes in the wake of China’s success from Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) (Huang 2016). In the case of Rwanda, we can look back to the region’s landscape to understand China’s interest. In addition to being at a critical location for trade routes across SSA, it is ripe for agricultural investment–a sector the PRC is looking to better secure due to food-producing sector shortages within the country (Liu 2023) and for the sake of developing business in SSA. Just as the initial colonial actors planned SGRs to help export Rwanda’s resources, China is looking to use the BRI to build up trade-benefiting infrastructures. Isaac Lawther (2017) argues that “China’s agricultural technology is affordable and easy to adapt to rural African environments,” which thus makes it ideal for Rwanda. Where nearly all of the non-urban environments are farms and a large portion of the population live in population, like many other developing nations, technologies which improve yield and efficiency.

It was during the period of struggle and stagnation following the Bugesera Invasion in Rwanda and surrounding regions when the PRC began to heavily invest infrastructurally. The most notable initial project was the TAZARA rail line connecting Tanzania and the DRC and built in a staggering 3-year period from 1970 to 1973 and used tens of thousands of Chinese and Tanzanian workers (Garlick 2023). During this time was also when the PRC and Rwanda officially signed to a friendly relationship (November 12, 1971) in addition to the PRC being recognized as the ruling entity of China to the UN (November 16, 1971). Their relationship hinged on it presenting as the first move towards a joint initiative for better education, health, and culture in Rwanda. However, it was primarily to have smoother negotiations “in various sectors of the economy” (Gierszewska 2020). Investment began shortly after; the China Road & Bridge Corporations (CRBC)–one of the largest civil firms operating in Rwanda–began designing as early as 1972 and groundbreaking as early as 1974 (CRBC 2024).

Specifically, the Kigali-Rusumo Highway was the first Chinese project, completed in 1977. Following projects, which kicked up especially since Kagame’s rule post-genocide, include the Parliament House Kininia Road, Kinyinyia Textile Mill Road, Rusizi-Rubavu Highway, and Kigali Genocide Memorial Centre Road. They furthermore trained local populations alongside funding the construction or refurbishment of a stadium, 2 convention centers, an airport, irrigated paddy fields in multiple regions, 3 hospital facilities, a cement factory, and upwards of 3 other agricultural processing centers. The most important takeaway from the infrastructural, cultural, and economic investment China has in Rwanda is its staggeringly similar parallels to colonial and postcolonial Germany and Belgium. To return back to colonial Belgium’s ten-year plan for economic and social development, China, directly completed projects which the Belgian forces could not or did not have the time to complete, but also is executing projects whose nature are not only identical, but are being successfully executed in an even more indirect manner. Close ties between the governments, as will be discussed shortly, help these BRI projects be painted in veils of “development” benefiting local populations, where in reality, many are used by Chinese firms or African ones with Chinese partners. The agricultural sectors which the PRC is developing and investing in in Rwanda, as Yun Sun (Kuo 2016) describes is “to create more market space for Chinese agricultural companies, more recognition that the Chinese are the true friend of African countries, and international recognition that China is a responsible stakeholder.” Essentially, farmers, both Rwandan and Chinese, are unknowingly playing into the PRC’s goal to create self-sufficient businesses which cyclically train new workers and expand production–all of whom will be reliant on large infrastructural corridors which are being developed. At its core, this business model is also neocolonial as Rwandan businesses, primarily in agriculture, require Chinese aid connections but in turn help develop Chinese business.--money which is then reinvested to support the cycle.

Conclusion: Thus, the Preludes to Chinese Control of Africa

Since Rwanda, like China, is an authoritarian regime–and has been one since its independence, relationships between the two nations, while peaceful, are teetering on a fine balance. Since both regimes rule strongly and have differing national goals respective to their nation and peoples, Grimm & Hackenesh (Grimm & Christine 2019, p.176) argue that “it thus seems that [Rwanda] should not be getting too close to Beijing, as that would increase the risk of being overlooked.” This is because Rwanda's commodity exports are presently not beneficial to China–who is undoubtedly the larger actor in the partnership–and if the PRC was hindered from development of economic sectors beneficial to its goals, they are likely to disengage from the region (Ibid.). However, with an estimated US$146 million in CCP investments since 1971 and further investment from smaller private Chinese firms alongside it (Gu & Carty 2014), development in Rwanda largely hinges on its relationship with the PRC–underscored by the fact that Rwanda’s GDP growth also depends on trade with China despite the major imbalance in import-exports between the two nations (favoring the PRC) (Lisimba & Parashar 2020).

China, as controlled by the CCP’s global agenda has, thus, become a neocolonial and, more appropriately, a neo-imperialist actor in Rwanda. Its aid holds Rwanda at the whim of Chinese interests, which not only has solidified the foundations of what infrastructures are prioritized in contemporary Rwandan development, but could spell out the landscape of the nations–especially its economy–in the coming years (Ibid.). Despite the BRI not being at the forefront of CCP interest, infrastructure development will continue and if no effort is made on from internal, and to some extent, external actors to regulate the quality and distribution of projects, Rwanda’s development with face severe imbalance, hindering the nation from evolving past its current agricultural-dominant economy. With no “technical capacities necessary to construct high-tech infrastructure on the scale required to transition the country from a predominantly agricultural society to a middle-income state with a focus on ICT” (Information and Communications Technology) (Hamersma 2021, p.282-283) as desired in Rwanda’s Vision 2020 and Vision 2050, it seems the country will remain stagnant and China’s control over economic sector will continue to encroach further and further.

Bibliography

African Development Bank Group. Africa Infrastructure Development Index (AIDI), 2022, 2022. https://infrastructureafrica.opendataforafrica.org/pbuerhd/africa-infrastructure-development-index-aidi-2022.

Anami, Luke. “China Back to Funding SGR Connecting Kenya and Uganda.” Nation Media Group, May 20, 2024. https://www.theeastafrican.co.ke/tea/business/chinese-back-to-funding-sgr-connecting-kenya-and-uganda-4627208.

“Approved Project: Construction of Central Corridor Standard Gauge Rail (SGR) of the Dar Es Salaam – Isaka – Mwanza and Isaka – Kigali / Keza – Gitega – Musongati / Tabora - Kigoma/Uvinza - Musongati ‐ Gitega (with Extension to Eastern DRC).” Program Infrastructure Development for Africa (PIDA), 2024. https://pp2.au-pida.org/approved-project/entry/i9lbh/.

Baker, Randall. “Reorientation in Rwanda.” African Affairs 69, no. 275 (1970): 141–54. https://doi.org/https://www.jstor.org/stable/719877.

Burns, Latoya Matthews. “The Rwandan Genocide and How Belgian Colonization Ignited the Flame of Hatred.” Department of History and Government College of Arts and Sciences Texas Women’s University, 2014, 1–104.

Chad, Peltier. “China’s Logistics Capabilities for Expeditionary Operations.” U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, April 15, 2020. https://www.uscc.gov/research/chinas-logistics-capabilities-expeditionary-operations.

Cohen, Jerome Alan. “China and Intervention: Theory and Practice.” University of Pennsylvania Law Review 121, no. 3 (January 1973): 471–505. https://doi.org/10.2307/3311300.

Coulibaly, Brahima S, Dhruv Gandhi, and Lemma W Senbet. “Is Sub-Saharan Africa Facing Another Systemic Sovereign Debt Crisis?” Africa Growth Initiative at Brookings, April 2019.

Dezenski, Elaine K, and Josh Birenbaum. “Tightening the Belt or End of the Road? China’s BRI at 10.” Foundation for Defense of Democracies, February 27, 2024. https://www.fdd.org/analysis/2024/02/27/tightening-the-belt-or-end-of-the-road-chinas-bri-at-10/.

Dorsey, Learthen. “The Rwandan Colonial Economy, 1916-1941.” Michigan State University, 1983. https://doi.org/https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/rwandan-colonial-economy-1916-1941/docview/303276954/se-2.

“Economy and Business.” Republic of Rwanda, 2024. https://www.gov.rw/highlights/economy-and-business.

Eder, Thomas S. “Belt and Road Forum: ‘Chinese Companies Are Clearly the Main Beneficiaries of BRI Projects.’” Mericator Institute for China Studies, April 24, 2019. https://merics.org/en/press-release/belt-and-road-forum-chinese-companies-are-clearly-main-beneficiaries-bri-projects.

Garlick, Jeremy. Advantage china: Agent of change in an era of global disruption. London, United Kingdom: Bloomsbury Academic, 2023.

“German East Africa.” Städtische Museen Freiburg, 2024. https://www.freiburg.de/pb/,Len/1335945.html.

Gierszwska, Wioleta. “Relations Between China and Rwanda.” Selected Socio-Economic and International Relations Issues in Contemporary Asian States, 2020. https://doi.org/10.15804/kon20215.

Grimm, Sven, and Christine Hackenesch. “China and Rwanda – Natural Allies or Uneasy Partners in Regime Stability?” China’s New Role in African Politics, October 21, 2019, 164–79. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429422393-11.

Gu, Jing, and Anthony Carty. “China and African Development: Partnership Not Mentoring.” IDS Bulletin 45, no. 4 (July 2014): 57–69. https://doi.org/10.1111/1759-5436.12093.

Hamersma, Eco. Rwanda’s Place on the Digital Silk Road: Discussing Rwanda Vision 2020 from the Perspective of Chinese Development Assistance, 2021.

Heijden, Marco van der. “Orientalism in Rwanda.” Bachelor Thesis Human Geography Radboud University Nijmegen, July 2010, 1–45.

Huang, Yiping. “Understanding China’s Belt & Road Initiative: Motivation, Framework and Assessment.” China Economic Review 40 (September 2016): 314–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2016.07.007.

Jie, Yu, and Jon Wallace. “What Is China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)?” Chatham House, December 19, 2022. https://www.chathamhouse.org/2021/09/what-chinas-belt-and-road-initiative-bri.

Kiriama, Herman O. “Urban Development and the East African Railways.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of African History, October 23, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190277734.013.1264.

Kuo, Lily, and Alicia Chen. “Chinese Workers Allege Forced Labor, Abuses in Xi’s Belt and Road Program.” The Washington Post, April 30, 2021. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/china-labor-belt-road-covid/2021/04/30/f110e8de-9cd4-11eb-b2f5-7d2f0182750d_story.html.

Kuo, Lily. “China Is on a Mission to Modernize African Farming-and Grow a Market for Its Own Companies.” Quartz, November 17, 2016. https://qz.com/africa/788657/a-chinese-aid-project-for-rwandan-farmers-is-actually-more-of-a-gateway-for-chinese-businesses.

Lawther, Isaac. “Why African Countries Are Interested in Building Agricultural Partnerships with China: Lessons from Rwanda and Uganda.” Third World Quarterly 38, no. 10 (June 16, 2017): 2312–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2017.1333889.

Lisimba, Alpha Furbell, and Swati Parashar. “The ‘State’ of Postcolonial Development: China–Rwanda ‘Dependency’ in Perspective.” Third World Quarterly 42, no. 5 (September 22, 2020): 1105–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2020.1815527.

Liu, Zongyuan Zoe. “China Increasingly Relies on Imported Food. That’s a Problem.” Council on Foreign Relations, January 25, 2023. https://www.cfr.org/article/china-increasingly-relies-imported-food-thats-problem.

Mayersen, Deborah. “‘Fraternity in Diversity’ or ‘Feudal Fanatics’? Representations of Ethnicity in Rwandan Presidential Rhetoric.” Patterns of Prejudice 49, no. 3 (May 27, 2015): 249–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/0031322x.2015.1048980.

“Modern History: Sub-Saharan Africa.” Council on Foreign Relations, February 8, 2022. https://education.cfr.org/learn/learning-journey/sub-saharan-africa-essentials/modern-history-sub-saharan-africa.

Murphy, Dawn C. China’s rise in the Global South: The Middle East, Africa, and Beijing’s alternative world order. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2022.

Nantulya, Paul. “The Growing Militarization of China’s Africa Policy.” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, December 2, 2024. https://africacenter.org/spotlight/militarization-china-africa-policy/.

Newbury, David. “Precolonial Burundi and Rwanda: Local Loyalties, Regional Royalties.” The International Journal of African Historical Studies 34, no. 2 (2001): 255–314. https://doi.org/10.2307/3097483.

Nyabiage, Jevans. “How Chinese Loans Help Fuel African Military Spending.” South China Morning Post, May 9, 2022. https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/3176951/how-chinese-loans-help-fuel-african-military-spending?module=perpetual_scroll_0&pgtype=article.

Office, U.S. Government Accountability. “China’s Foreign Investments Significantly Outpace the United States. What Does That Mean?” U.S. GAO, September 4, 2024. https://www.gao.gov/blog/chinas-foreign-investments-significantly-outpace-united-states.-what-does-mean.

Paul, Axel T. Comparing colonialism: Beyond European exceptionalism ed. by Axel T. Paul and Matthias Leanza. Edited by Matthias Leanza. Leipzig: Leipziger Universitätsverlag, 2020.

Potter, Johan. “Re-Imagining Rwanda: Conflict Survival, and Disinformation in the Late Twentieth Century.” Cambridge University Press, September 26, 2002, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511491092.001.

Preston, Robert. “Kenya Secures More Chinese Funding for Standard Gauge Railway.” International Railway Journal, May 21, 2024. https://www.railjournal.com/freight/kenya-secures-more-chinese-funding-for-standard-gauge-railway/.

Prunier, Gérard. The Rwanda Crisis: History of a genocide. London, United Kingdom: Hurst & Company, 1997.

Purdeková, Andrea, and David Mwambari. “Post-Genocide Identity Politics and Colonial Durabilities in Rwanda.” Critical African Studies 14, no. 1 (June 21, 2021): 19–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681392.2021.1938404.

Reyntjens, Filip. “Understanding Rwandan Politics through the Longue Durée: From the Precolonial to the Post-Genocide Era.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 12, no. 3 (April 12, 2018): 514–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/17531055.2018.1462985.

“Rwanda Office.” China Road & Bridge Corporation (CRBC), 2024. https://www.crbc.com/site/crbcEN/RwandaOffice/index.html.

Said, Edward W. Orientalism. New York: Pantheon Books, 1978.

Singiza, Dantès. “Ruzagayura, Une Famine Au Rwanda Au Cœur Du Second Conflit Mondial*.” Institut D’histoire Ouvrière Économique et Sociale 97 (September 7, 2012): 1–7. https://doi.org/https://www.ihoes.be/PDF/Analyse97DSingiza.pdf.

Stapleton, Timothy J. A history of genocide in Africa. Westport, Conneticut: Greenwood, 2017.

A ten year plan for the economic and social development of the Belgian trust territory of Ruanda-Urundi. New York, New York: Belgium: Ministère des colonies, 1952.

“Unit 1: The Reforms of Belgian Rule in Rwanda.” Rwanda Basic Education Board eLearning, April 11, 2021. https://elearning.reb.rw/course/view.php?id=65§ion=1.

United Nations Development Programme. “Breaking the Gridlock: 2023/2024 Human Development Report.” Human Development Report, March 13, 2024, 1–324. https://doi.org/10.18356/9789213588703c003.

Vansina, Jan. Antecedents to modern Rwanda: The Nyiginya Kingdom. Oxford: James Currey, 2005.

Wang, Christopher Nedopil. “China Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) Investment Report 2023.” Green Finance & Development Center, March 19, 2024. https://greenfdc.org/china-belt-and-road-initiative-bri-investment-report-2023/?cookie-state-change=1731965130820.

Wang, Christopher Neophil. “Countries of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).” Green Finance & Development Center, 2024. https://greenfdc.org/countries-of-the-belt-and-road-initiative-bri/.

Wong, Tessa. “Belt and Road Initiative: Is China’s Trillion-Dollar Gamble Worth It?” BBC News, October 17, 2023. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-67120726.

Zadi, Awa Princess E. “The Hamite Must Die! The Legacy of Colonial Ideology in Rwanda.” City University of New York Academic Works, 2021. https://doi.org/https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/4153.